From the Coop Report 2022: A dangerous new world

Epochal changes and the impact on lifestyles. The 2022 edition of the Coop Report paints a complex picture where, despite everything, food spending holds up.

The information in this article is extracted from the Coop Report 2022, Consumption and Lifestyles of the Italians of Today and Tomorrow.

Pandemic, climate crisis, war, inflation. The simultaneous summation of a series of terrible and unforeseen events has in the early months of 2022 triggered a perfect storm whose effects we see spreading day by day.

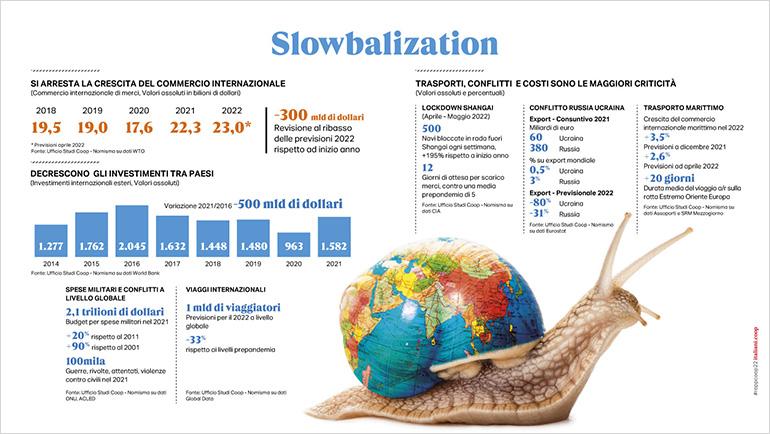

A dangerous new world is looming on the horizon in which democracy is increasingly at risk (40 percent of global GDP comes from unfree countries), food poverty is growing, international trade is declining, and the climate emergency is now a dramatic everyday occurrence. With world GDP downward from +5.7 percent in 2021 to +2.9 percent in 2022, Italy is heading for a worsening growth forecast that sees +3.2 percent in 2022 falling to +1.3 percent in 2023. This is an economic picture weighed down by the post covid, which still affects many aspects of people’s lives, and the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the consequences of which are most evident in the soaring inflation that leads to an average loss for Italian families of around 2,300 euros. The one described by the Coop Report is the Italy of 2022, which on balance turns out to be more vulnerable, with the middle class increasingly struggling, a section falling behind (24 million people in 2022 experienced at least one hardship) and a sharp rise in the area of outright poverty (+ 6 million in the last year).

Contextually, the scissor of inequality grows, with luxury brands at +17/19% in the first quarter of 2022 (Il Sole 24 Ore Altagamma Bain) where 48% of the sample, due to the sense of instability, postpones large expenditures in appliances and cars, but also the purchase of the first house, not forgetting the small renunciations of the everyday superfluous.

A price chain on the rise

Against this backdrop, retail faces a market on which great unknowns weigh heavily and where 2022 is seen as one of the most difficult years ever.

Indeed, on the one hand, retail companies have to cope with the exceptionally high industrial price increases and the explosion of high energy prices, and on the other hand, they cannot ignore the difficulties of final demand and the need to cushion the effect of rising costs on the consumer’s ability to purchase. The increase in the prices of food goods sold by industry to large-scale retail chains have risen by 15 percent over last year, while on-sale inflation has clocked in at just over +9 percent.

For that matter, the differential between the purchase and sale price marks a -5.7 percent to the detriment of large-scale retail chains. Growing in particular are commodities such as seed oil at +40.9%, olive oil at +33.1%, pasta at +30.9% and flour +25.4%. Added to this are energy costs, which were worth 1.7 percent of sales in 2019 and are now projected to grow threefold with 4.7 percent in 2022 and 5.2 percent in 2023.

The strength of discount stores

Against a backdrop where large-scale retailers are further reducing their margins, which stand at 1.5 euros for every 100 spent by consumers, it is the discount store that is once again registering the greatest growth, while there is a steady decline in the hypermarket concept.

Looking at e-grocery, a key player in the lockdown, according to the Coop report it seems to have lost propulsive momentum, standing at very low values compared to the rest of Europe with figures at 2.9 percent in 2021 and forecasts of no more than 6 percent when looking at 2030. These figures are quite different from those of other European areas such as the United Kingdom, which went from 12 percent to 19 percent or France from 8.6 percent to 16 percent.

Food market holds up

Good news, however, comes from Italians’ traditional focus on the quality of food spending, which is helping to stem the decline in consumption. The food supply chain has not been spared from inflation, which in Italy, however, sees lower figures than the European average with +10 percent compared to, for example, Germany’s +13.7 percent.

According to the COOP Report, there are therefore 24.5 million Italians who, despite rising prices, are not willing to compromise in their food choices and who in the coming months plan to decrease the quantity but not the quality of their food.

Also returning is the cooking time experienced in lockdown; more time is spent in preparing meals and engaging in experimenting with new dishes. The clearest demonstration of the new value attributed to Italians’ food, however, is the surprising lack of a net fall in purchases (-0.1% negative mix effect in the first half-year) which, instead, was the first response to difficulties in previous economic crises. It is likely that, with a worsening of the situation, Italians will indeed react in such a way again, but today the shopping trolley is no longer a resource from which to draw from to finance other forms of consumption but, rather, a bastion to protect. It’s perhaps one of the main legacies of the pandemic.

At the same time, the food that we refuse to renounce appears to be most of all the simple and basic kind, without frills and superfluities; “Italianness” and sustainability are essential elements that are eroding the market for other features that were more sought after in the past.

As a result, there are fewer ethnic foods, various “without” foods (gluten-free, etc.) and ready-to-eat foods on our tables, and also organic foods appear to have suffered a setback.